Archives Experience Newsletter - September 12, 2023

A Promise from the Founders

Welcome to the Archives Experience debut series: A Republic, If You Can Keep It. In celebration of Constitution Day, we’re chronicling the creation of this document—but these aren’t the stories we’ve all heard before. Instead, we’ll look at how the National Archives holdings show just how close we came to an entirely different form of government and how “We the People” triumphed in the end.

Do you know what one of your most absolute rights is in the Constitution? It’s one that cannot be challenged in court–in fact, it’s a guarantee.

The Founding Fathers were not champions of democracy. It’s true that they were eager to shed a monarchical system that dated back hundreds of years, but they weren’t so comfortable with democracy–or what they saw as “mob rule”–either. So a republic it was. But how did we get to this place, a middle ground between absolutism and popular sovereignty? Learn more about this right enshrined in the Constitution…

History Snack

The United States is a republic, as stated by article 4, section 2 of the U.S. Constitution:

The United States shall guarantee to every State in this Union a Republican Form of Government, and shall protect each of them against Invasion; and on Application of the Legislature, or of the Executive (when the Legislature cannot be convened) against domestic Violence.

This article is called the “guarantee clause” because it promises that the government of this country will always be a republic, elected by popular sovereignty and maintained by majority control. The core of popular sovereignty is free and fair elections, and the peaceful transition of power; this was begun by George Washington when he stepped down from the presidency after two terms in 1796, establishing an unwritten precedent that has been honored to this day.

During the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia between May and September 1787, the delegates argued long and hard about what form of government the new nation should take. The Articles of Confederation that had governed the United States after the Revolutionary War ended had created a very weak central government that had no power to manage trade, print a single currency, or pass or enforce laws that all the states would universally agree to. The result was a nation on the verge of collapse.

Despite our thoughts of them as stalwart champions of democracy, the Founding Fathers were an elite class—they feared mob rule and debated vigorously about how the new government should be structured. Most of them were utterly opposed to a direct democracy, in which the electorate determines policy themselves instead of having representatives (presumably wiser and better informed than they) do it for them. Our Founding Fathers, decidedly did not trust the masses to make the decisions that would steer the ship of state.

Federalist No. 10

NARA’s Founders Online

That said, as we discussed in last week’s newsletter, they also eventually decided they didn’t want a hereditary monarchy in the United States, either. Thus, the notion of a representative democracy emerged as the best option for the new nation.

James Madison wrote in Federalist No. 39,

[W]e may define a republic to be, or at least may bestow that name on, a government which derives all its powers directly or indirectly from the great body of the people, and is administered by persons holding their offices during pleasure, for a limited period, or during good behavior. It is ESSENTIAL to such a government that it be derived from the great body of the society, not from an inconsiderable proportion, or a favored class of it; . . . It is SUFFICIENT for such a government that the persons administering it be appointed, either directly or indirectly, by the people; and that they hold their appointments by either of the tenures just specified. . . .

Federalist No. 39

NARA’s Founders Online

Explaining his stance to Gouverneur Morris, another participant in the Convention who wrote the Preamble to the Constitution, Alexander Hamilton stated, “But a representative democracy, where the right of election is well secured and regulated & the exercise of the legislative, executive and judiciary authorities, is vested in select persons, chosen really and not nominally by the people, will in my opinion be most likely to be happy, regular and durable.”

Alexander Hamilton on the merits of a representative democracy

NARA’s Founders Onine

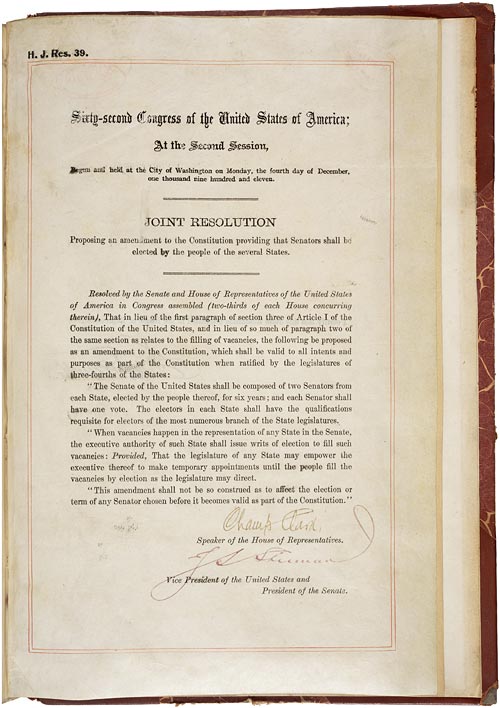

As time passed, “the people” have become more involved in our democracy. As the Constitution was originally written, the number of members of the House of Representatives was determined by the population of the states, while each state had the same number of senators, two, and they were chosen by the state legislatures. This proved problematic, however, when politicization of state legislatures resulted in empty seats because the legislators could not decide on who to send to the Senate. The 17th amendment to the Constitution, passed by Congress on May 13, 1912 and ratified on April 8, 1913, authorized voters of individual states to directly elect their senators to Congress.

Senatorial deadlocks cartoon

National Archives Identifier: 6010878

1826 House Resolution for Direct Election of Senators

National Archives Identifier: 1943384

Joint resolution introducing the 17th amendment

National Archives Identifier: 1408966

17th amendment

NARA’s Milestone Documents