Archives Experience Newsletter - October 3, 2023

Obsessed

History lovers of today: what was the topic that got you, as a kid, interested in history? What started as a quick lesson in school that turned into a fascination you couldn’t learn enough about? Your younger self always hoped it would come up in conversation so you could share the latest fun fact or piece of knowledge you’d gleaned. Now, you can see what records the National Archives has about your childhood history niche interest…

In this issue

The Sinking of the Titanic

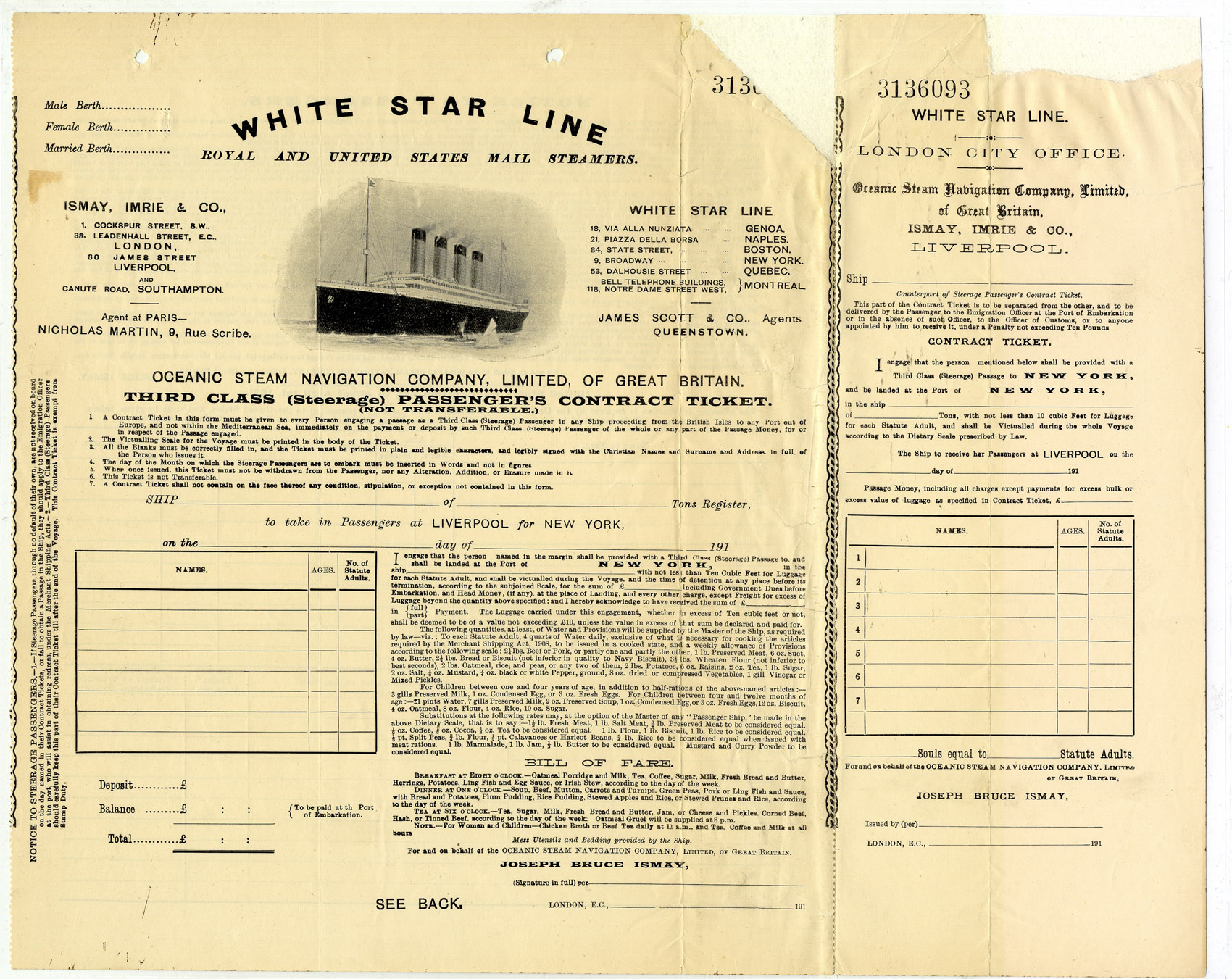

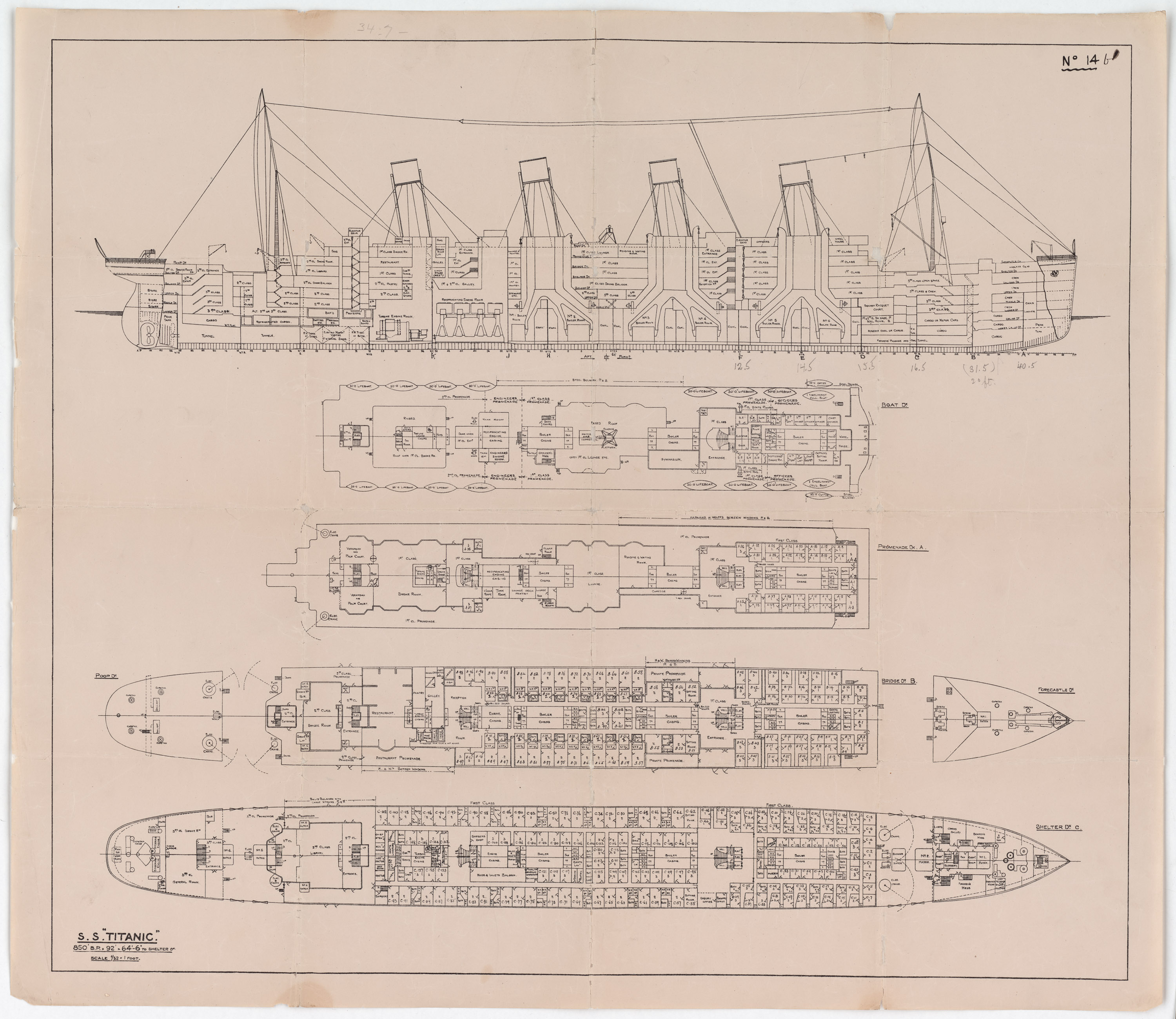

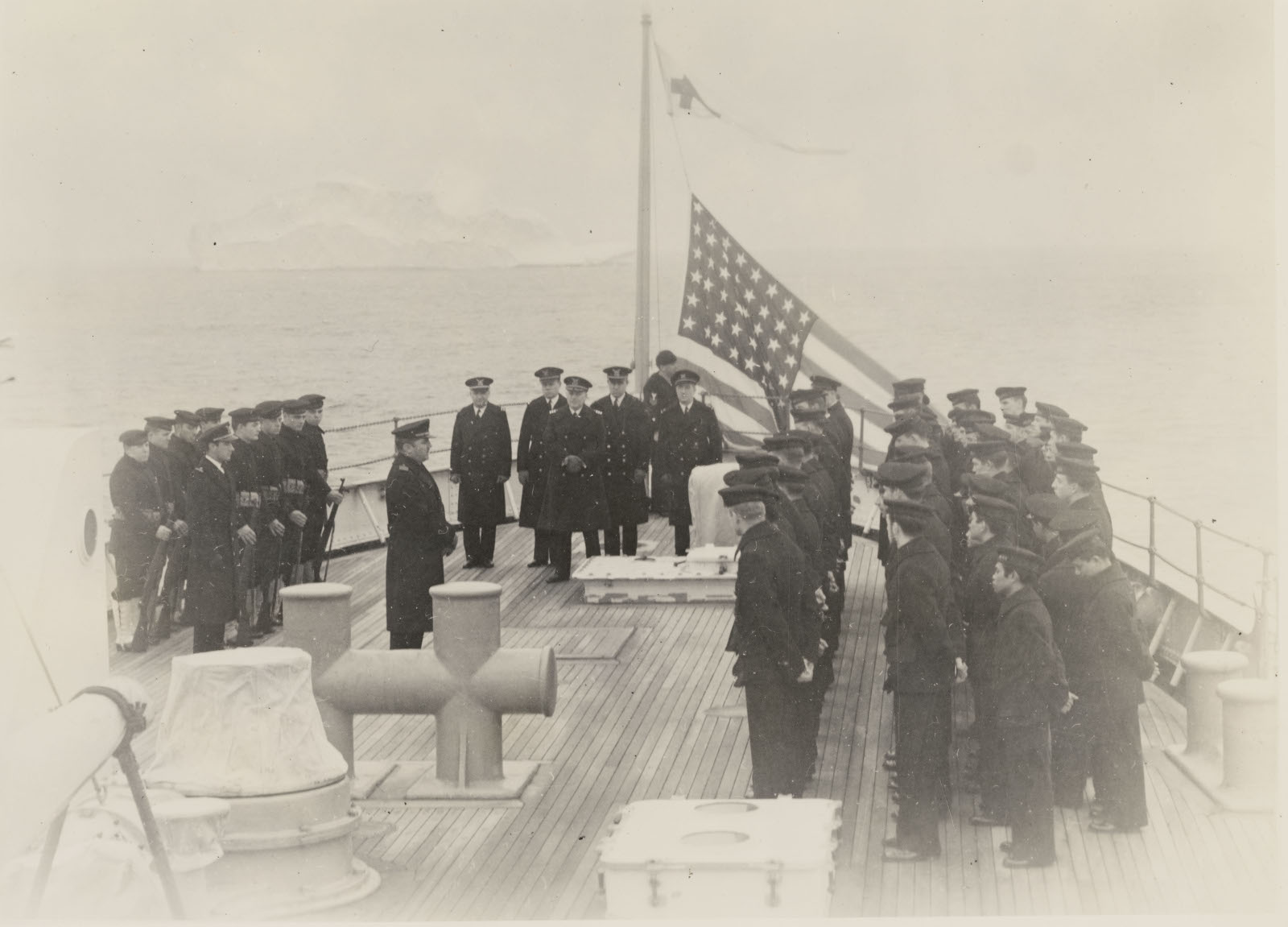

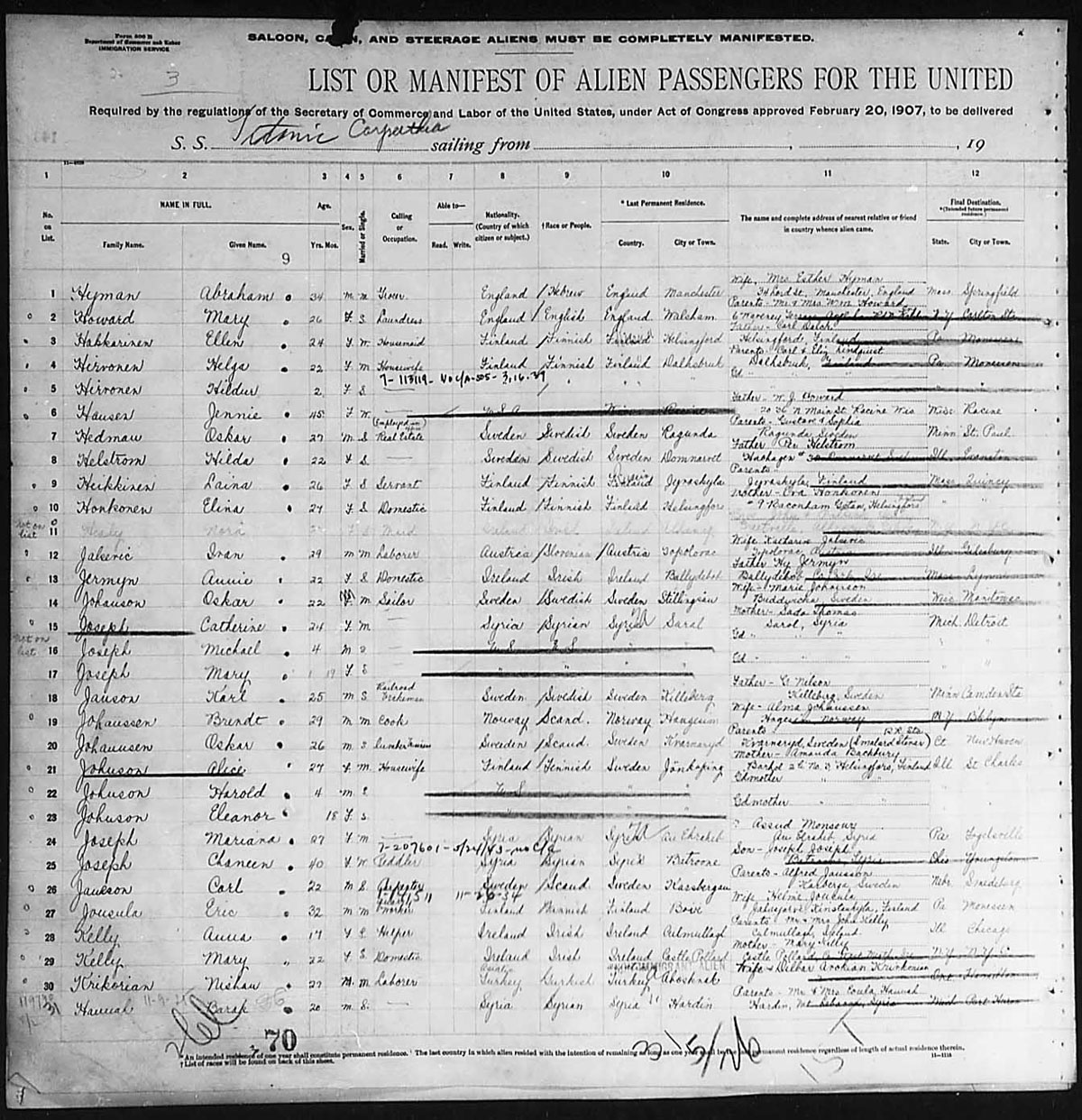

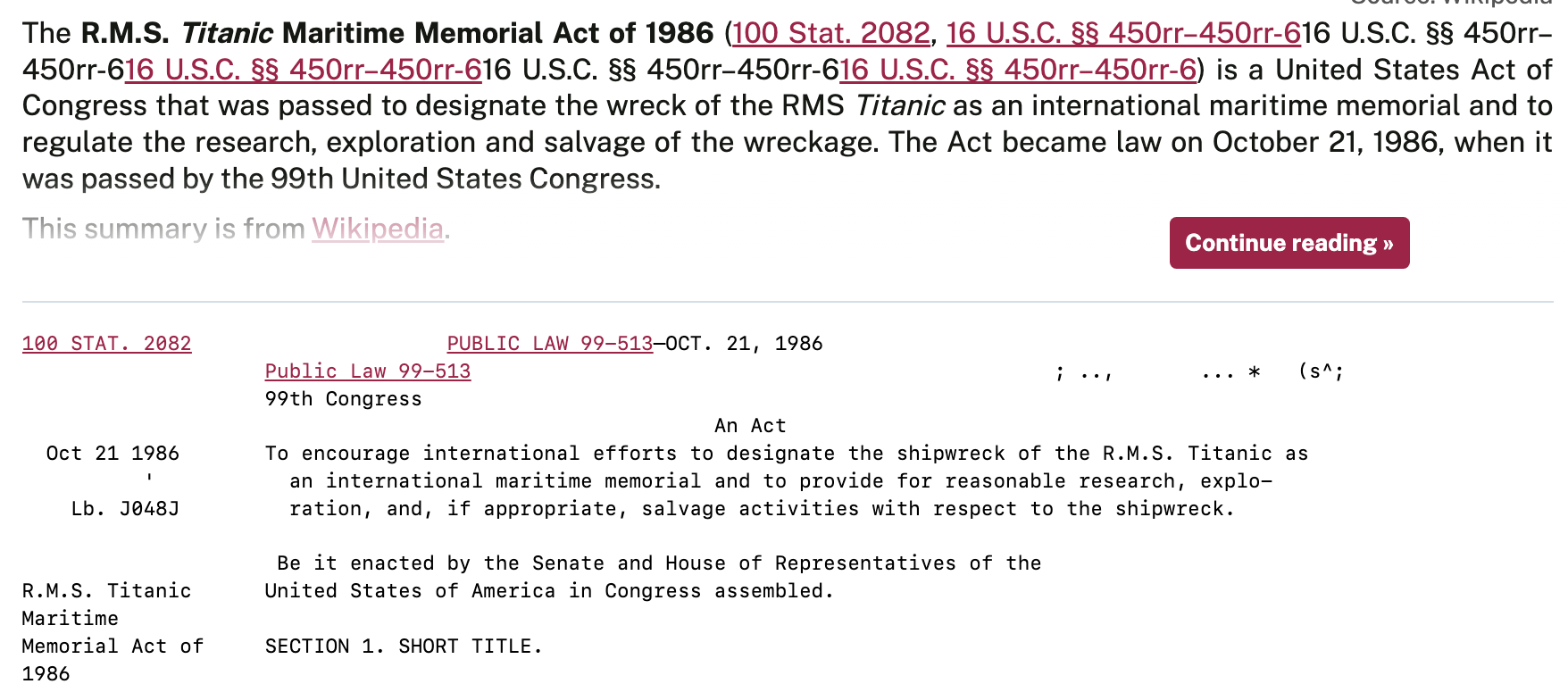

Operated by the British White Star Line, RMS Titanic was hailed as “unsinkable” because it had watertight compartments and remotely activated watertight doors. Nevertheless, as we all know, the ship hit an iceberg on its maiden voyage from Southampton, England, to New York City on April 15, 1912, in the north Atlantic Ocean. She sank like a stone in less than three hours. More than 1,500 of the estimated 2,224 passengers and crew aboard her died, mainly because she was carrying only 20 lifeboats, less than half the 48 she was equipped for and well less than half enough to carry everyone aboard to safety.

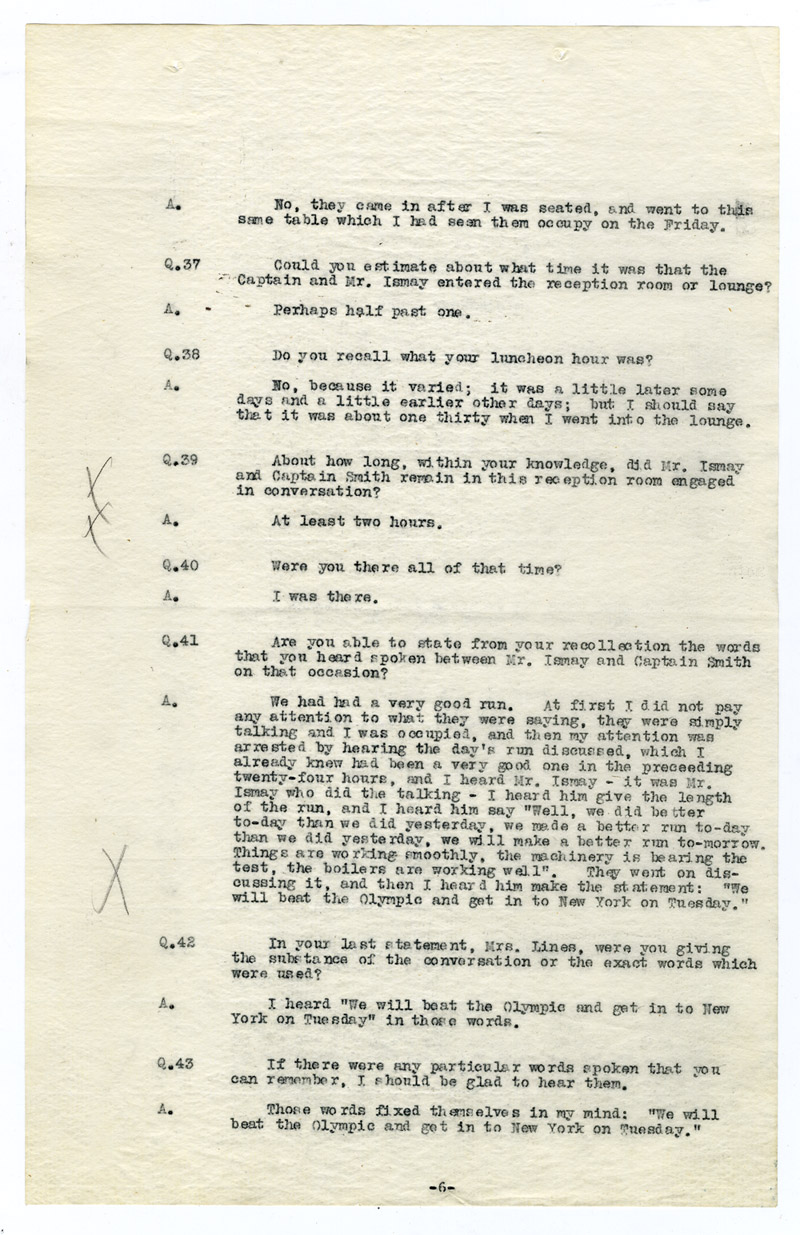

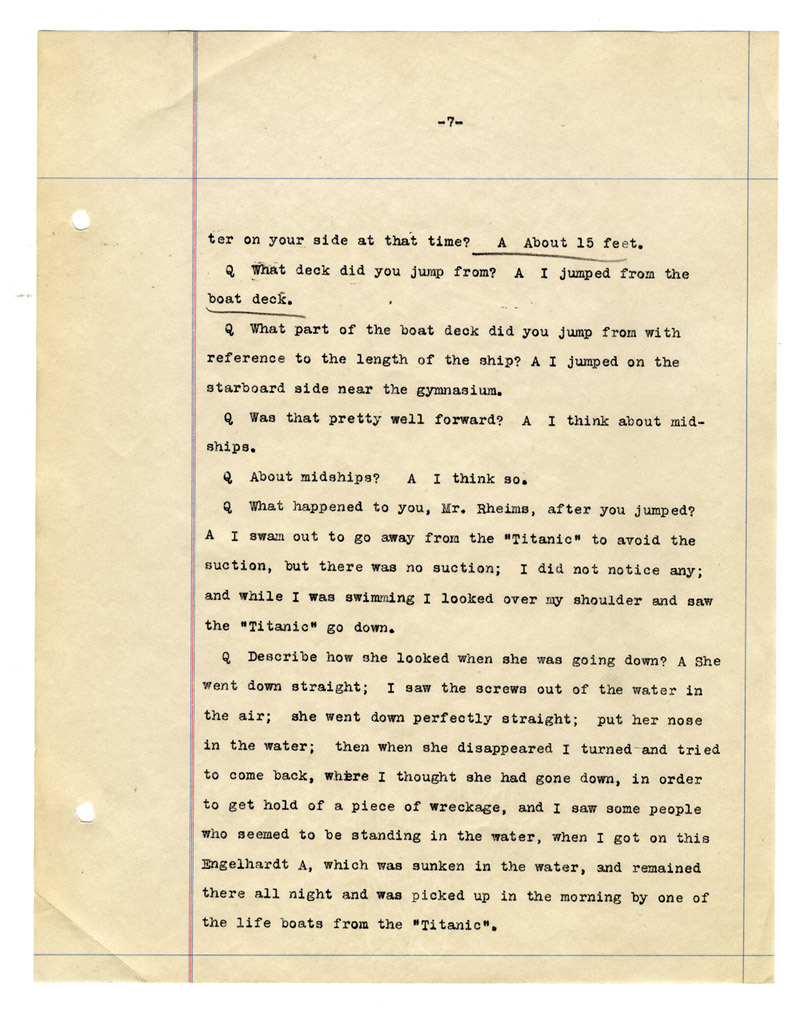

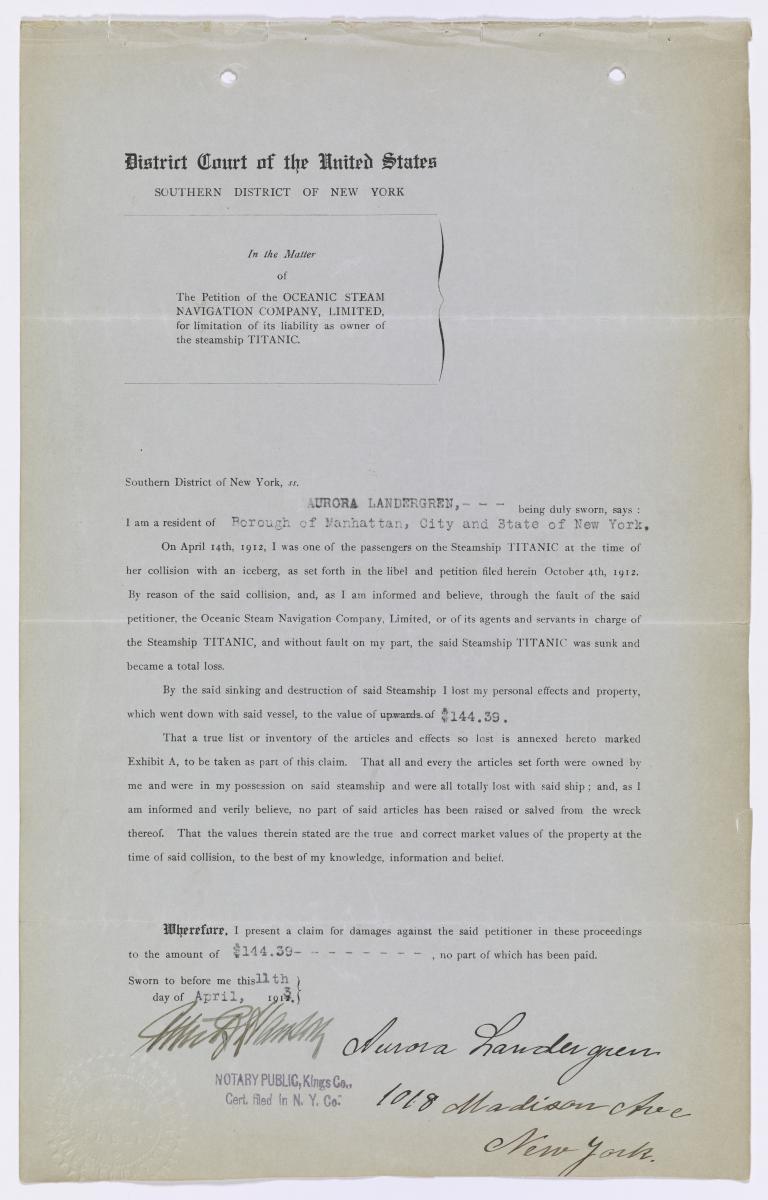

The National Archives is the repository of a rich trove of documents that illuminate fascinating facts about the tragedy of the Titanic. Of course, there’s a pile of photographs of things like the reception room on the ship and the lifeboats and the good ship Carpathia, which came to the rescue of the survivors. But more obscure and illustrative records also abound in the holdings. Consider, for instance, the testimony of Elizabeth Lines, who overheard Bruce Ishmay, the chairman and director of the White Star Line, tell Captain Edward John Smith, “We will beat the Olympic and get into New York on Tuesday.” (It might interest you to learn, if you don’t already know, that Ishmay survived the sinking of his ocean liner, while Captain Smith went down with the ship.) Or the petition of Aurora Landergren, filed more than a year after the ship went down, for $144.39 as compensation for the property she had lost. (That’s $4,523.62 in 2023 dollars.) These documents come from lawsuits that were filed in district courts, which is why you can find them in the holdings today.

Ancient Egypt

President Hoover with King Tut

Source: Obama White House website

What kid hasn’t at least flirted with a passing fancy for ancient Egypt? How did they build the pyramids? What about those gruesome mummies? And who can resist the fascination of Tutankhamun, the fabulously rich boy king who died so young?

On February 16, 2023, NARA marked the 100th anniversary of the opening of King Tut’s tomb in Thebes, Egypt. Although NARA doesn’t have actual records about ancient Egypt, it holds several records of the 100th anniversary event, including a newsreel about the opening of the tomb in 1923 and footage of the popular exhibition Treasures of Tutankhamun being unloaded at the shipyard in Norfolk, Virginia, by U.S. Navy personnel.

Plus, in a presidential tribute, Herbert Hoover named his beloved dog King Tut, pictured above.

Universal Newsreel: Egypt digs for ancient treasure

(1 minutes 10 seconds, NO SOUND)

Arrival of the exhibit in Norfolk, Virgina

(2 minutes 32 seconds, NO SOUND)

The Salem Witch Trials

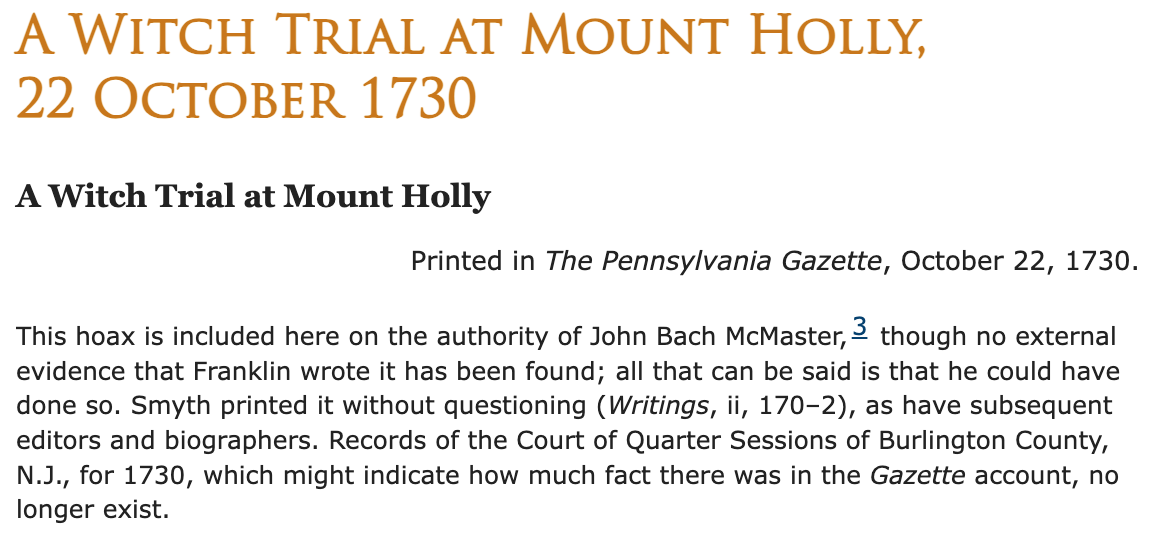

1730, A Witch Trial at Mount Holly – Source: NARA’s Founders Online

NARA’s Founders Online

The Salem, Massachusetts, witch trials are a subject that has long attracted the interest of young history buffs, probably at least partly because of the horrifying possibility of people being falsely accused of crimes punishable by death. From early 1692 to mid-1693, more than 200 people were accused of practicing witchcraft, and 20 were executed for their supposed crimes.

The trouble all began when the daughter of the Reverend Samuel Parris, Elizabeth, age 9, his niece Abigail Williams, age 11, and Ann Putnam, age 12, began screaming, making strange noises, and throwing things. They accused three women who, we must point out, were in no position to oppose them, of casting spells over them: Sarah Good, a homeless beggar, Sarah Osborne, a poor, elderly woman, and Tituba, a Caribbean woman enslaved by the Parris family.

Even after being questioned for several days, both Good and Osborne denied the charges, but Tituba eventually confessed, “The devil came to me and bid me serve him.” With that, the floodgates opened, and hundreds of people were tried on charges of practicing witchcraft. Twenty were executed, and five died in prison. It wasn’t until the fall of 1692, when his own wife was questioned as a suspected witch, that Governor William Phips came to his senses and put a stop to the trials. By the next spring, he had pardoned all the prisoners. Finally, in 1957, Massachusetts formally apologized for the events of 1692. After 329 years, on June 28, 2022, the last suspect in the Salem Witch Trials, Elizabeth Johnson, was fully exonerated by the state.

The National Archives has in its holdings the National Register of Historic Places for the Salem Village Historic District, which describes the significance of the area in great detail. It is also home to a photograph of the house of George Jacobs, who was hanged for witchcraft in Salem in 1692; the Massachusetts Historical Commissions’ documentation of the house of John Proctor, who was also hanged for witchcraft; a photograph of the house of Jonathan Corwin, a judge in the trials; and a photograph of an old witch house in Salem.

Pirates on the High Seas

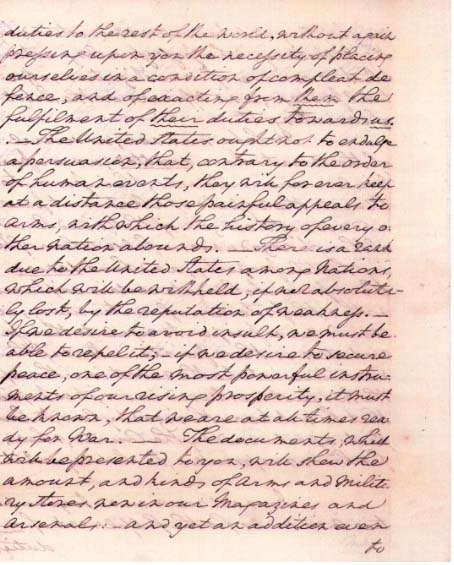

Washington’s 1793 annual address to Congress addressing the Barbary Pirate problem

Now, slap on your tricorn hat, put your cutlass between your teeth, run up the Jolly Roger, and dive into the treasure chest of NARA’s holdings. There’s so much to examine on the subject that we’ll just concentrate on the young United States’ brush with piracy right after the signing of the Treaty of Paris, when the Barbery pirates of Algeria rather suddenly became a serious threat.

Captain Richard O’Bryen’s letter to Thomas Jefferson

Source: NARA’s Prologue Magazine

While the colonies were part of the British empire, the pirates were protected by the British crown, and during the Revolutionary War, France had granted them protection, but once the war was over and the United States was its own master, the pirates set their sights on capturing American ships sailing in the Mediterranean Sea. In October 1784, Moroccan pirates captured the Boston brig Betsey, which was ransomed two years later, but the Algerian pirates who took the Boston schooner Maria and the Dauphin, from Philadelphia, within a week of one another in late July and early August 1785 refused to release them and their crews without payment of considerable monies—$59,496, to be exact, which amounts to nearly $1,883,200 today.

O’Bryen letter to Jefferson outlining pirates’ ransom rates–July 12, 1790

Source: NARA’s Prologue Magazine

The United States’ problem was that under the Articles of Confederation, the weak central government could not tax the states to raise money, so it was helpless to secure the funds to free the ships and their crews. The National Archives holds a series of documents that address the situation, including several letters from Richard O’Bryen, captain of the Dauphin, to Thomas Jefferson, Jefferson’s message to Congress transmitting O’Bryen’s letter to that body, and George Washington’s address to Congress in 1793 about the Barbery pirate problem.

Jefferson’s message to the Senate transmitting O’Bryen’s letter

Source: NARA’s Prologue Magazine

O’Bryen, his crew, and the crews of the Maria and several other ships ended up being held captive until September 1795, when the United States finally negotiated peace with Algiers and ransomed the ships and 119 crew members. The grand total was $642,000, plus $21,000 in annual tribute ($5,643,706(!) and $5,710,000(!) today), and four naval vessels, one of them a 36-gun frigate. O’Bryen and his crew were held hostage for more than 10 years, in all.

Proposal to use force against the Barbary States, 1790

Thomas Jefferson to Yusuf Qaramanli of Tripoli, 1801

Source: NARA’s Founders Online