Archives Experience Newsletter - August 15, 2023

The General

Washington. Grant. Patton. Eisenhower. There are figures in military history so great that their names alone tell a story. From the birth of a nation to its near breakup, to a global battle against the Axis powers, these generals have not only borne witness to history, but shaped it.

General Douglas MacArthur was one of those figures. Although he was not without controversy, there’s no talking about 20th-century conflict without acknowledging MacArthur’s impact on two World Wars, the Cold War, and America’s rise as a superpower.

It’s August 14, 1945; the nuclear age has begun, and negotiations for Japan’s surrender are in motion. At the center of these events: General Douglas MacArthur…

In this issue

History Snack

End of an Empire

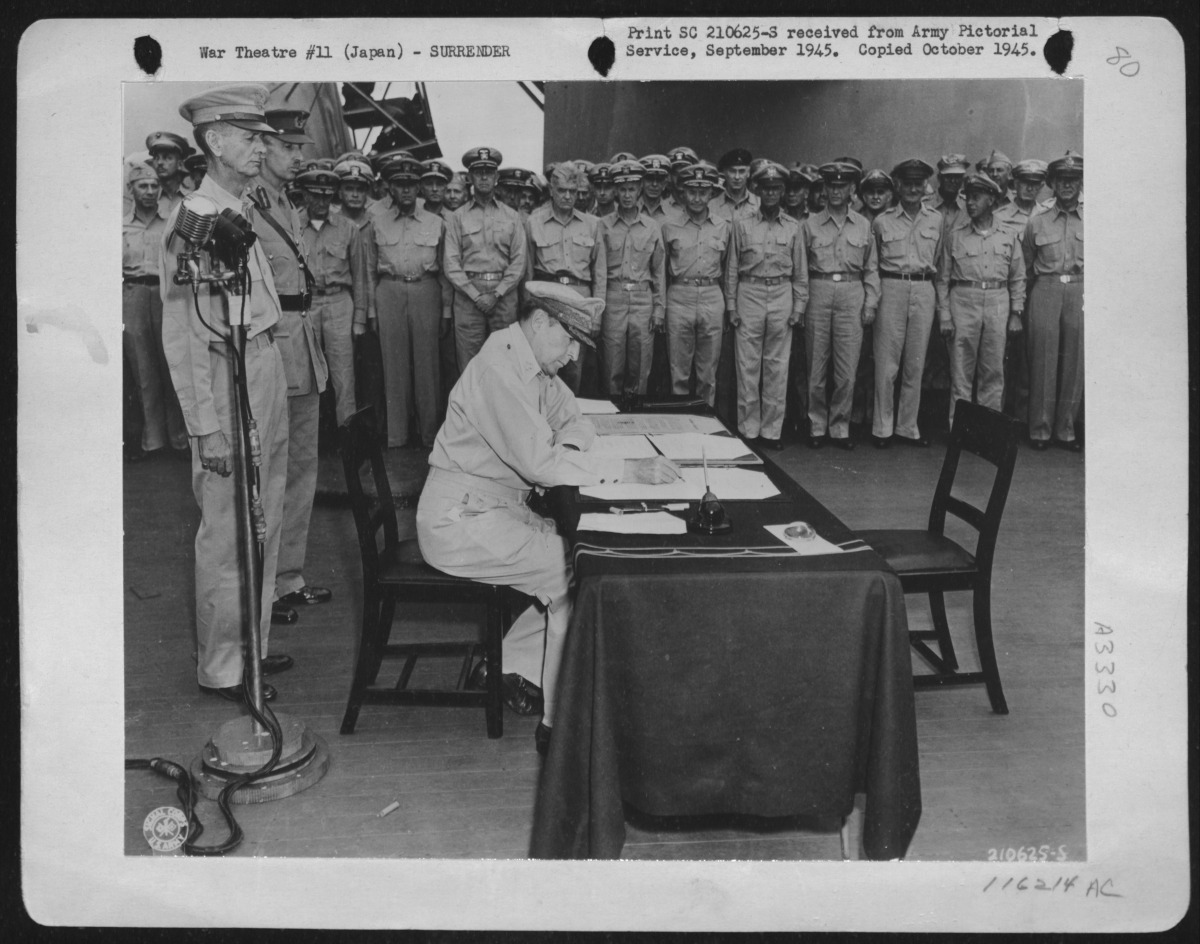

On September 2, 1945, General Douglas MacArthur, the Supreme Commander of the Allied Forces, presided over the ceremony in Tokyo Bay, on the deck of the U.S.S. Missouri, by which the empire of Japan formally surrendered to the Allied Nations and thus ended World War II. Representatives from Japan signed the Japanese Instrument of Surrender first, and then representatives from the nine Allied powers signed in turn. For MacArthur, the ceremony marked not only the end of the war, but also the beginning of his remarkable tenure in directing the reshaping and rebuilding of Japan.

Japanese surrender ceremony aboard the USS Missouri

(9 minutes 22 seconds)

National Archives Identifier: 79773

A Life in Command

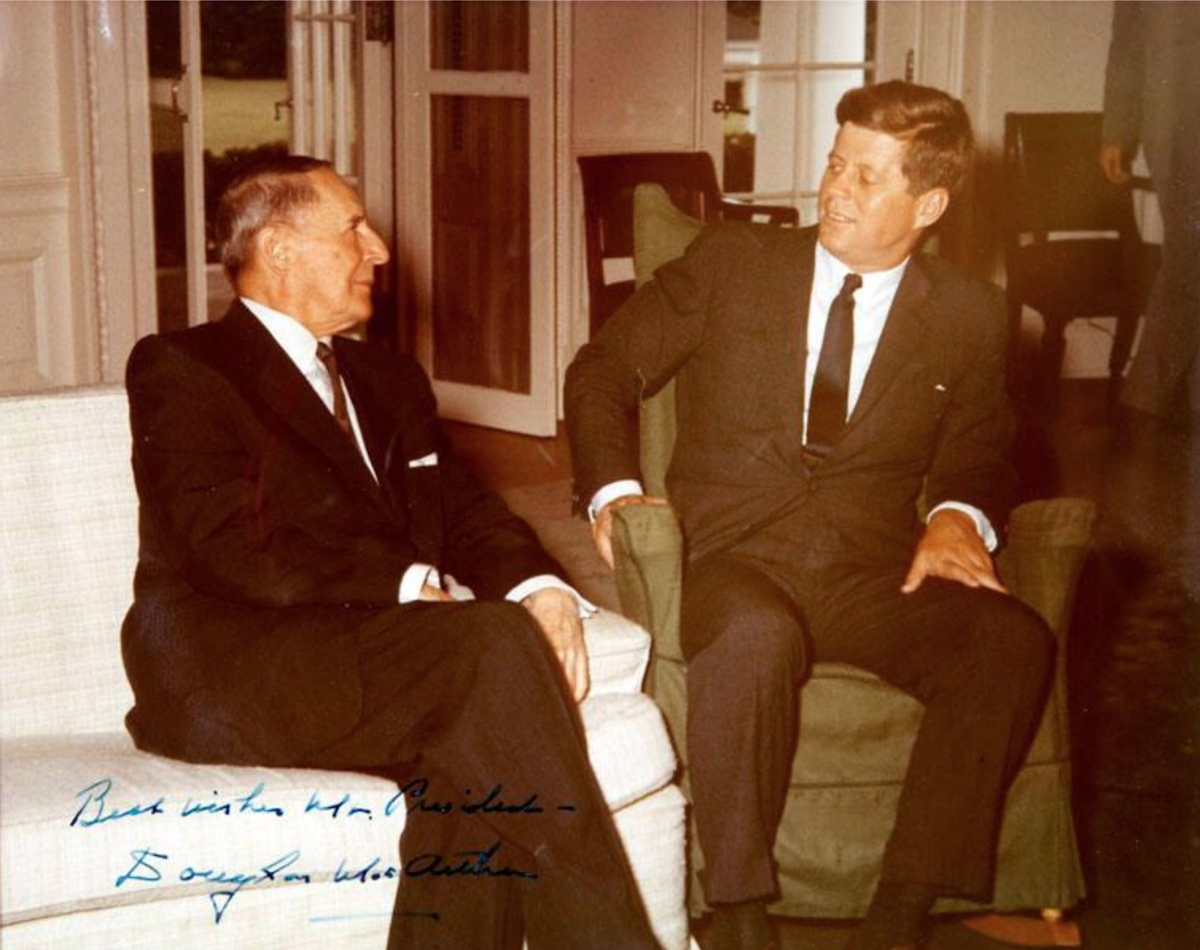

General MacArthur

Source: JFK Library

MacArthur Oath of Office

National Archives Identifier: 57296286,

item 5

Douglas MacArthur had been born into a military family in Little Rock, Arkansas, on January 26, 1880. His father, Arthur MacArthur, Jr., was the commander of infantry units in various outposts in New Mexico that were assigned to protect settlers and railroad workers from supposedly hostile Indian tribes. In 1893, his father was posted to San Antonio, Texas, and Douglas attended the West Texas Military Academy, where, for the first time in his life, he excelled in academics and military discipline. Upon graduation, Douglas received an appointment to the United States Military Academy at West Point. In 1903, he graduated first in his class as his father, by then a general, looked on.

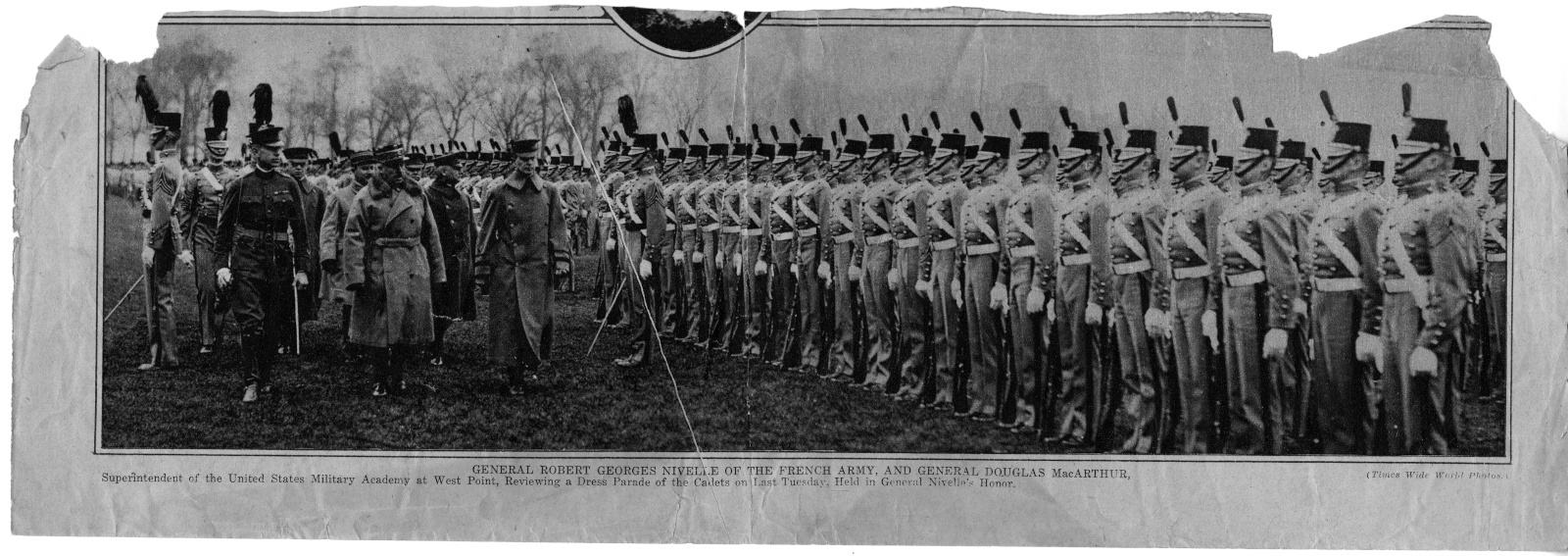

From the academy, Douglas was stationed in the Philippines, the first of several such assignments throughout his career and the beginning of his lifelong connection with Asia. It was also the beginning of a pattern of stellar performances followed by less than remarkable ones. Next, he worked with his father on a series of tours throughout Asia during which he did very well, but back in the States, he performed very poorly on an engineering assignment in Milwaukee in 1907. When his father died in 1912 and Douglas was transferred to Washington, D.C., so he could take care of his mother, he again excelled under the guidance of Chief of Staff Leonard Wood, and he went on to achieve battlefield brilliance during World War I in France. Returning from Europe, he was appointed superintendent of West Point. He succeeded in modernizing the academy in many ways, but he also incurred the ire of Chief of Staff John J. Pershing when he married Louise Cromwell Brooks, with whom Brooks had had an affair. Pershing promptly sent the MacArthurs packing to the Philippines, where Douglas was happy, but Louise was not. Their marriage did not survive the stress of the assignment.

MacArthur’s acceptance of Colonel of Infantry, 1917

National Archives Identifier: 57296286,

item 7

After yet another stint in the Philippines, MacArthur was appointed Army Chief of Staff by President Herbert Hoover in 1930. Although this was a plum assignment, he bungled it when the Bonus Army, a group of 43,000 U.S. Army veterans, their families, and sympathetic groups gathered in Washington, D.C., in 1932, to demand that their service bonus certificates be redeemed for cash early. Most of the veterans had been out of work since the beginning of the Great Depression. Led by Walter W. Waters, a former Army sergeant, the Bonus Army camped out on the lawn of the U.S. Capitol building.

The U.S. Attorney General ordered the Bonus Army removed on July 28, 1932. The Washington police tried to remove them, met with resistance, and shot and wounded two veterans, who later died. President Hoover ordered the Army to remove the marchers, and MacArthur complied, driving out the veterans, their wives, and children at gun- and saber-point and burning their belongings. The whole episode was a public relations fiasco that contributed to Hoover losing the 1932 presidential election.

Letter from FDR to MacArthur upon arrival in the Philippines

Source: FDR blogs

Despite their differing politics, President Franklin D. Roosevelt kept MacArthur on as Army Chief of Staff until 1935, when he accepted the invitation of his old friend Manuel Quezon, the president of the Philippines, to create a Philippine army. Roosevelt approved the assignment, and MacArthur shipped out for Manila. Aboard the SS Hoover, he met Jean Marie Faircloth, a socialite from Tennessee, whom he married a few years later. They soon became the parents of Arthur MacArthur IV, and Douglas was very happy in both his professional and his personal life.

MacArthur as Supreme Commander, South Pacific

National Archives Identifier: 2595319

General of the Army of the US

National Archives Identifier: 213259898

But when Japan bombed Pearl Harbor, the American forces in the Philippines were the next targets, and by December 24, 1941, MacArthur, his family, and his immediate command were forced to withdraw to Australia. The rest of his command fell to the Japanese by April 1942, and thousands of American and Filipino prisoners of war were summarily executed or died as they were transported in unventilated boxcars and then forced to march to Camp O’Donnell on Luzon island. Many more died because of the squalid conditions in the camp.

Meanwhile, General George Marshall decided that General MacArthur should receive the Congressional Medal of Honor, even though he did not strictly meet the criteria for the award. Despite this issue, MacArthur received the medal on April 1, 1942.

Operating from Australia, and in concert with troops from that nation, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, and other countries, MacArthur directed a campaign through New Guinea and back up to the Philippines, to which he returned on October 20, 1944. The Allied troops succeeded in liberating Manila by March 1945. MacArthur succeeded in liberating the rest of the Philippines before the planned invasion of Japan in last summer of 1945, before the dropping of the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki forced Japan to surrender.

From the beginning of his work as the Supreme Commander of the Allied Forces, MacArthur chose to work with the existing Japanese government rather than depose it, including the emperor, whom most of the Japanese people considered a living god. He and his staff, operating sometimes by charm and sometimes by fiat, persuaded the Japanese to adopt a democratic form of government, instituted land reform that put property into the hands of many landless farmers who had worked it for generations, and helped the Japanese rebuild their war-torn countryside and prepare to enter the modern industrial world.

Reviewing French troops in 1919

National Archives Identifier: 75439409

MacArthur landing at Leyte, Philippines

Source: FDR blogs

MacArthur presents a Medal of Honor, 1944

MacArthur was also responsible for enforcing the sentences given out by the International Military Tribunal for the Far East, which in late 1945 convicted about 4,300 individuals for war crimes and sentenced about 1,000 to death and hundreds to life imprisonment. MacArthur interceded on behalf of the emperor of Japan and his family, insisting that forcing him to abdicate would cause violent protests and would require the help of a million soldiers to suppress them.

In 1948, despite still being stationed in Japan, MacArthur threw his hat in the ring for the Republican presidential nomination. He let the GOP leadership know that he would accept the nomination if it was awarded to him, but Thomas Dewey soundly defeated a wide field of competitors, including MacArthur, at the convention.

Compilation of Douglas MacArthur

(6 minutes 5 seconds)

National Archives Identifier: 23235

MacArthur in the South Pacific, March 1951

National Archives Identifier: 205001253

MacArthur 15 miles north of the 38th parallel, April 1951

National Archives Identifier: 531405

Translated citation from the Republic of Korea giving MacArthur the “Order of Military Merit”

National Archives Identifier: 299770

MacArthur handed governance of Japan back to the Japanese in 1949, but he was still in Japan on June 25, 1950, when North Korea invaded South Korea and started the Korean War. The United Nations Security Council authorized the U.S. government to choose a commander, and the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff unanimously picked MacArthur. The general soon stabilized the situation on the Korean peninsula, but he then decided that the only way to end the conflict was to engage directly with the Chinese. As soon as U.S. and Korean troops approached the North Korean border, Chairman Mao’s troops started pouring across it, and MacArthur was forced to withdraw his troops southward. Seoul fell to the Chinese in January 1951, but the U.S. troops, commanded by Lt. General Matthew Ridgeway, retook the South Korean capital in March.

The Last Battle

MacArthur dismissal

National Archives Identifier: 145807650

Pentagon Statement on Relief of MacArthur

National Archives Identifier: 165976577

At that point, President Truman felt ready to negotiate a peace agreement, but then it came out that MacArthur had been secretly communicating with the Tokyo embassies of Spain and Portugal that he wanted to scale up the conflict into an all-out war with China. At that point, Truman ordered Ridgeway to relieve MacArthur of his commands on April 10, 1951, on the grounds that he had made public statements on policy matters, although technically he had not disobeyed an order. Truman’s popularity took a huge hit in the polls, but the President felt it was a step he had to take.

Returning stateside, MacArthur lived out the rest of his life quietly with his wife Jean in New York City. He counseled President John F. Kennedy in the aftermath of the Bay of Pigs invasion. In 1962, he received the Thanks of Congress, a special recognition that dates back to the Revolutionary War.

Ronald Reagan remarks at MacArthur corridor dedication–Pentagon

(Reagan’s remarks start at 16:53)

National Archives Identifier: 161344016

See Douglas MacArthur’s entire military file

National Archives Identifier: 57296286

General Douglas MacArthur died at Walter Reed Army Medical Center in Washington, D.C., on April 5, 1964. Confirming President’s Kennedy’s previous authorization, Lyndon Johnson stated that MacArthur should be buried “with all the honor a grateful nation can bestow on a departed hero.” His body was transported to New York City and lay in state at the Seventh Regiment Armory for about 12 hours before being taken by train to Union Station and then transported by a funeral procession to the Capitol building to lie in state. Approximately 150,000 people passed by his coffin.

General MacArthur was buried in Norfolk, where his mother was born and his parents were married. His funeral service was held on April 11 at St Paul’s Episcopal Church, and his body was buried in the rotunda of the Douglas MacArthur Memorial.

The Douglas MacArthur Story

(2 minutes)

National Archives Identifier: 2569682