Archives Experience Newsletter - August 16, 2022

The Path to Aloha

Birthdays can come with a lot of conflicting feelings. Some birthdays, like sixteen, eighteen, and twenty-one, are celebrations that mark new milestones, while others can leave you feeling reflective, nostalgic, or even sad. Most people don’t know about the Rainbow State’s mixed path to statehood, which finally became official on August 21 sixty-three years ago.

How did a kingdom of several islands become our fiftieth state? The road to statehood was long and treacherous, but it had more in common with its predecessors in the contiguous U.S. than you might think. Like many other states, the desire to annex Hawai`i was rooted in the availability of land, the friendly climate for crops like pineapple and sugarcane, and the financial interests of plantation owners. But there were also the interests of Native Hawai`ians, some of whom opposed statehood and others who pushed for it to escape the limbo of being a territory and to receive the same rights and freedoms that other Americans had.

Hawai`i’s journey to statehood spanned twelve presidents and two Native monarchs and involved hundreds of thousands of citizens who made their voices heard on both sides of the issue. Come along as we open up the Archives’ records about Hawai`i.

Patrick Madden

Executive Director

National Archives Foundation

A Fruitful Annexation…for Some

Map of the

territory of Hawai`i

Source: NARA’s Prologue blog

The modern history of Hawai`i is a harrowing tale of imperialism at its worst. Where the first humans migrated from to the rocky archipelago 2,000 miles southwest of the mainland United States is subject to considerable debate—they may have been Polynesians who sailed there from the Marquesas Islands around 1000 to 1200 C.E., migrants from Bora Bora or Raiatea, or sailors who crossed the Pacific Ocean in canoes from Tahiti. In any case, those who made Hawai`i their home developed a caste-based society founded on religious beliefs that emanated from the natural world. The islands and the surrounding waters were rich in plants and fish to feed and clothe them. Local chiefs ruled their settlements and defended them against their rivals.

Then in 1778, British explorer Captain James Cook sailed the HMS Resolution into Waimea harbor, Kauai, and everything changed for Native Hawai`ians. In very short order, traders, whalers, missionaries, and explorers from many nations were stopping at the islands to resupply their ships and persuade the Natives to change their religious beliefs. The Native Hawai`ians had no natural immunity to protect them against the diseases the Europeans brought with them. By 1890, the Native population had fallen from around 300,000 to less than 40,000 from the ravages of measles, tuberculosis, smallpox, typhoid, venereal diseases, cholera, and leprosy.

Native Hawai`i girls working in a fruit canning factory

National Archives Identifier: 522863

Prior to 1795, chiefs on all the inhabited islands had fought among themselves for dominance over the archipelago, but in 1795, King Kamehameha the Great defeated all the other chiefs and unified rule over all the islands. The monarchy he established remained in power until 1872. However, western religious and business interests grew ever more on the islands. Sugar was soon the most important agricultural product and the key export, and the plantation owners, who were from the U.S., became more involved in Hawai`ian politics. The last king of Hawai’i, David Kalākaua, was forced to sign a new constitution in 1887 that stripped him of his powers, denied Native Hawai`ians their rights, and installed a new cabinet of mostly foreign businessmen and politicians.

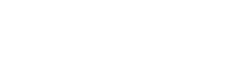

McKinley nomination of Sanford Dole to serve as Hawai`i governor

National Archives Identifier: 306337

Kalākaua died in 1891, and his sister Lili`uokalani ascended to the Hawai`ian throne. She introduced a new constitution that would have restored her powers and the rights of the Hawai`ian peoples, but the “Committee of Safety,” a group of nonnative U.S. businessmen and politicians led by Sanford Dole, overthrew the queen in a bloodless coup on January 17, 1893. Sanford Dole was a descendant of American missionaries, and he believed strongly that Hawai`ian culture and government should be westernized. He was named the president of the provisional government that petitioned the U.S. government to annex Hawai`i, but Lili`uokalani’s and Native Hawai`ians’ objections and changes in presidential administrations in the United States delayed that action.

View the Joint Resolution for the Annexation of Hawai`i

National Archives Identifier: 5730378

Furthermore, the Native Hawai`ians were not going down without a fight. They protested and resisted the overthrow of their queen and the annexation of their lands by a foreign power. An armed rebellion of the Hawai`ians in 1895 ended with its leaders and the queen being jailed. The queen and her people then took legal action, petitioning the U.S. Congress to protest annexation of their lands. Although public opinion was running in their favor, the sinking of the U.S.S. Maine in Havana Harbor on February 15, 1898, turned the tide against them. Realizing that the U.S. Navy could use the Hawai`ian islands as a staging ground for fighting the coming Spanish-American War, Congress annexed the Territory of Hawai`i on July 7, 1898. Sanford Dole was appointed the first governor of the territory.

Hawai`ian Coup

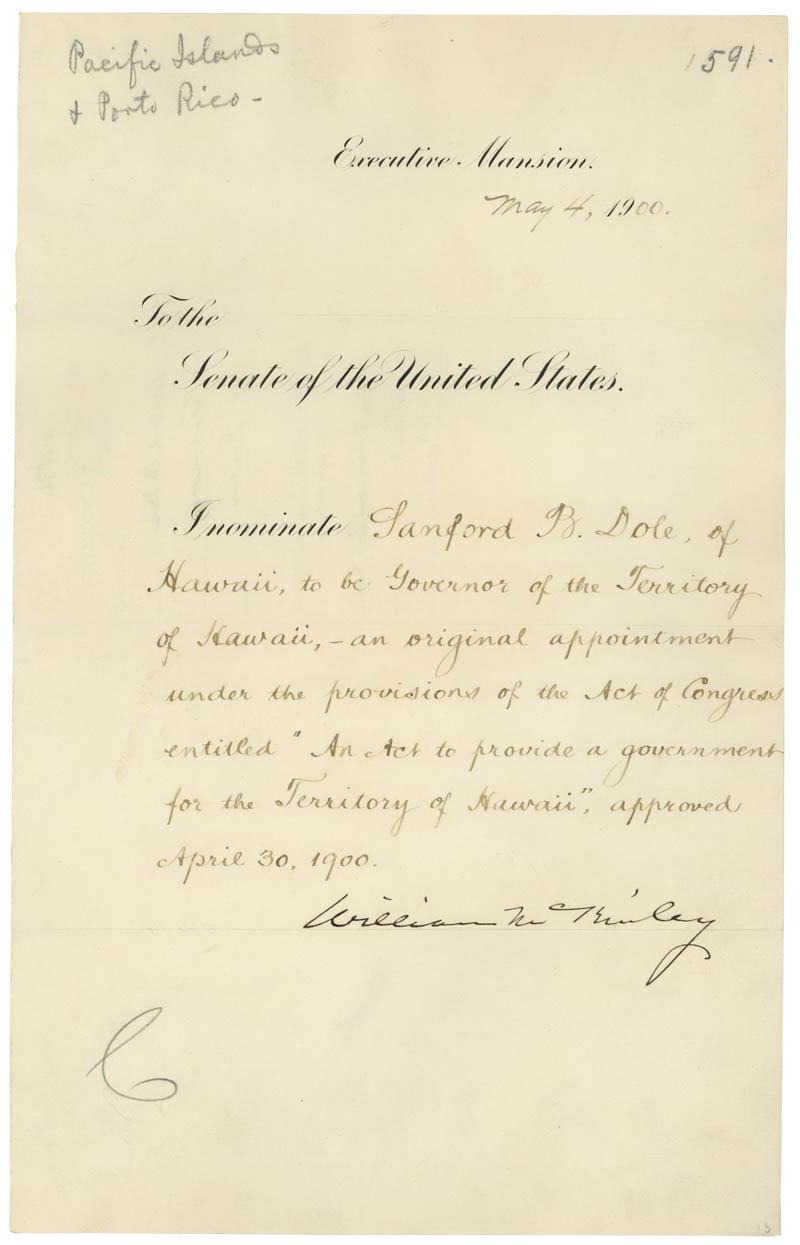

Petition against the annexation of Hawai`i

Source: NARA’s DocsTeach

The National Archives is the repository of this petition that was sent to Congress in 1897. It is nearly 600 pages long and was signed by more than 21,000 Native Hawai`ians at a time when the total population numbered less than 40,000.

Queen Lili`uokalani’s letter of protest

National Archives Identifier: 306653

The success of this protest movement was rooted in grassroots activism that took momentum after Queen Lili`uokalani was overthrown. Native Hawai`ians formed The Hawai`ian Patriotic League, which was split between the Hui Aloha `Aina (or women’s division) and the Hui Kālaiʻāina (men’s division). Between the two divisions, more than 21,000 signatures were gathered to petition against annexation.

This strong indication of Native sentiment helped persuade Congress to oppose the initial move to annex the islands. Unfortunately, this activism delayed, not prevented, annexation. The Hawai`ian islands were officially annexed on July 7, 1898, a move sanctioned by Congress.

Yes to the Aloha State

Berryman: “Uncle Sam – he wants me to bring him in”

National Archives Identifier: 6012445

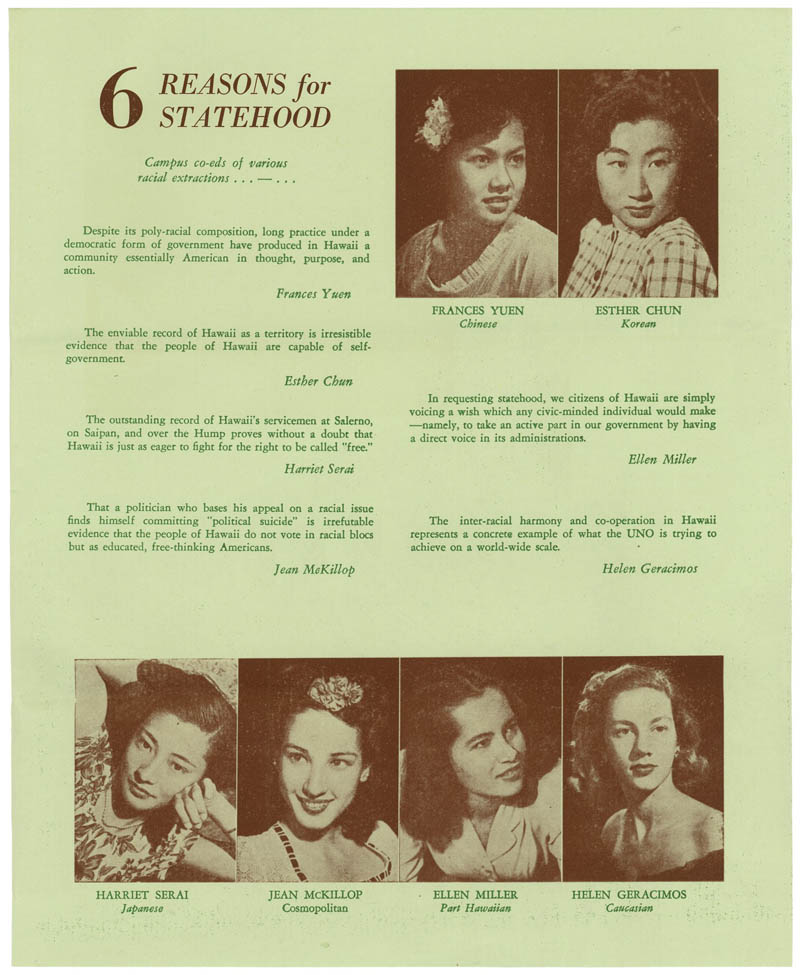

With the collapse of the Native population, migrant workers began to arrive on the islands to work on the sugar and pineapple plantations at the end of the nineteenth century. Most of them came from Japan, the Philippines, and China. Many people of European descent also lived on the islands.

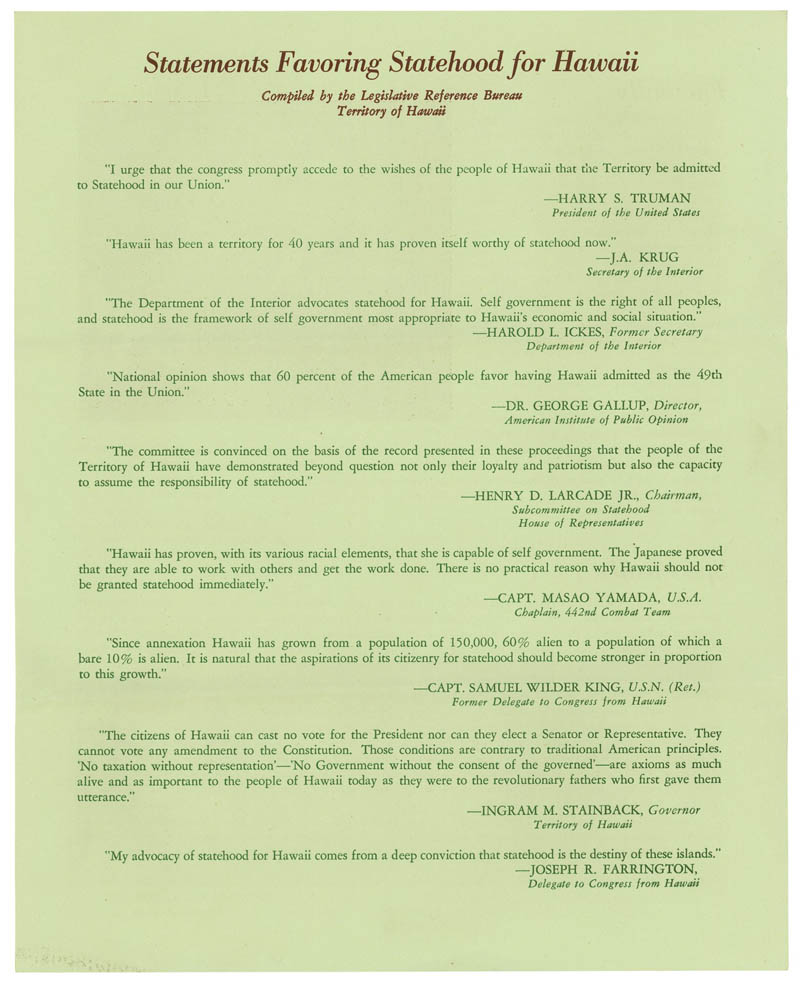

Hawai`i’s path to statehood, however, was long and circuitous. After it was annexed in 1898, it became a territory in 1900, but Native Hawai`ians and Congress both continued to oppose making the islands a state. The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, postponed action on the question even further.

This petition, signed by 116,000 individuals who supported statehood, was presented to the Senate on February 26, 1954. It most likely is an indication that the inhabitants of Hawai`i were tired of the legal limbo they had been living in for nearly sixty years. Hawai‘i’s bid for statehood was combined with Alaska’s, and Hawai`i became the fiftieth state in the union on August 21, 1959.

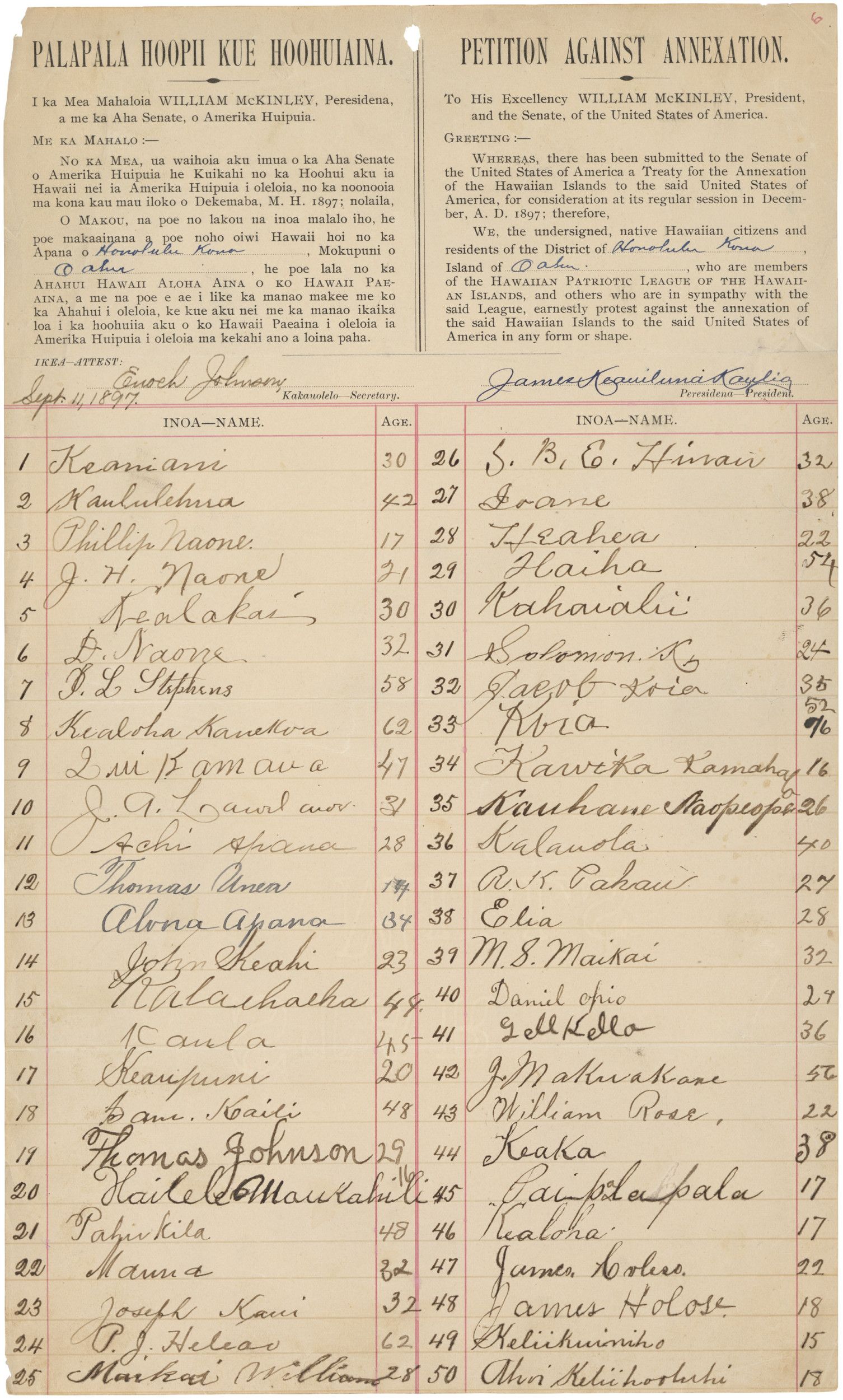

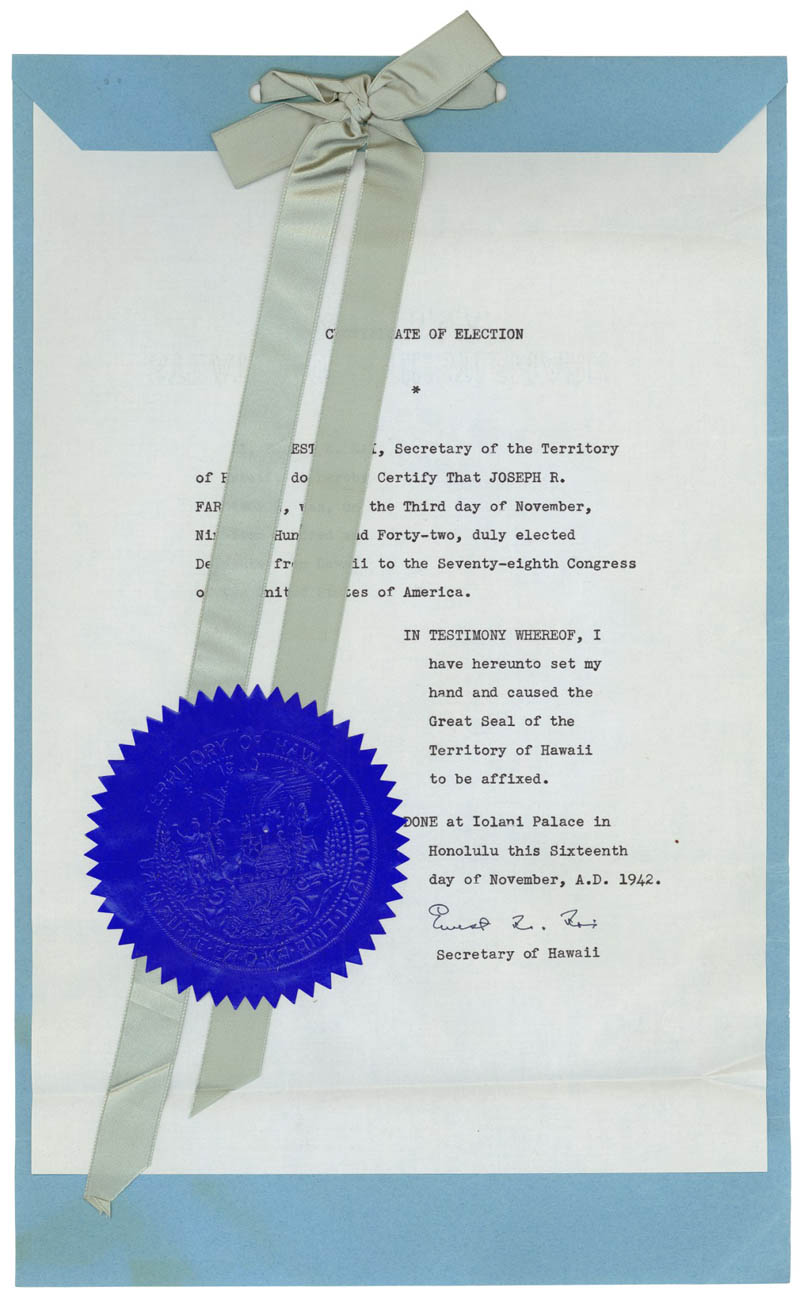

Certification letter of election Joseph Farrington as the Congressional delegate from Hawai`i Source: Source: NARA’s Center for Legislative Archives |

Farrington certificate of election Source: NARA’s Center for Legislative Archives |

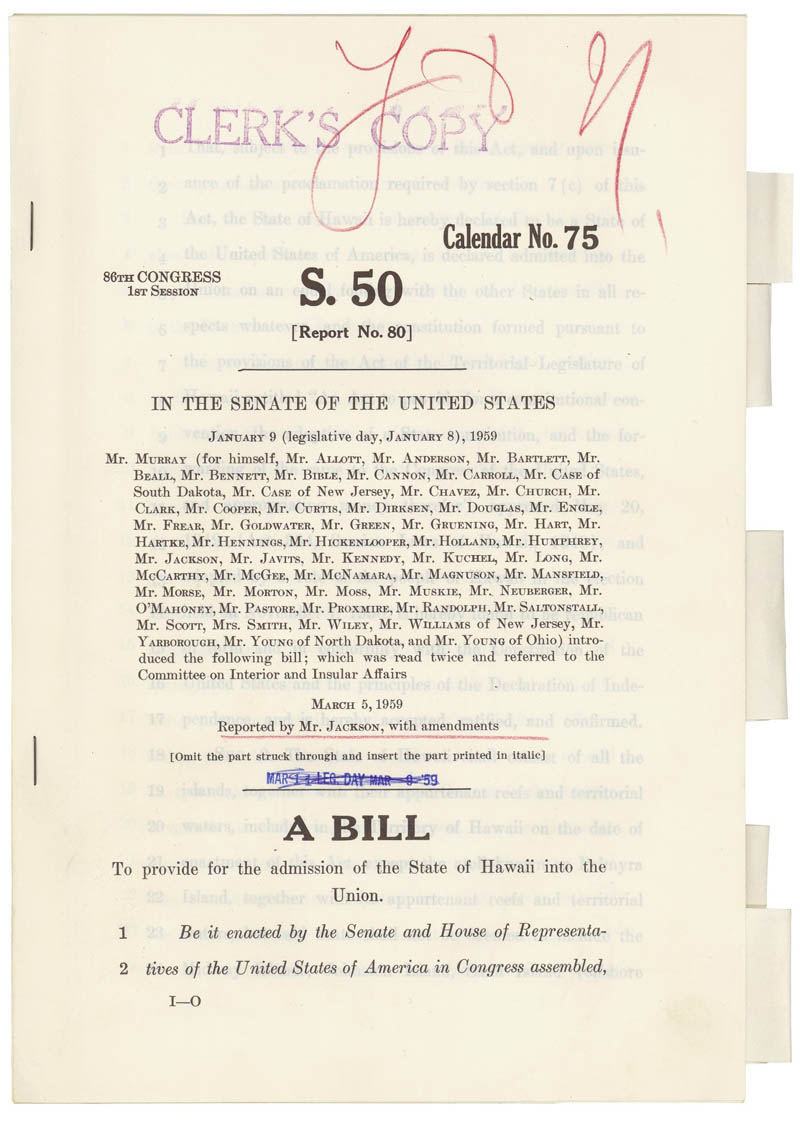

A Bill to admit Hawai`i into the union Source: NARA’s Center for Legislative Archives |

To view the text of a document or the full image, click on the image displayed above

The Big Kahuna

The Polynesians undoubtedly invented surfing, and they certainly brought it with them to the Hawai`ian islands, where Captain James Cook and his men observed the Native Hawai`ians riding their surfboards in the waves. To the Hawai`ians, surfing was a spiritual pursuit that began with the construction of the surfboard. Surfing was intimately tied to the individual’s position in the community, whether that person was royalty or commoner.

After Christian missionaries came to Hawai`i, the religious aspect of surfing was downplayed, and its popularity declined significantly. Surfing and hula were even outlawed under the “Committee of Safety” in order to stamp-out Native traditions. In the latter part of the nineteenth century, King Kalakaua, also called the Merry Monarch, revived hula and surfing. After the turn of the twentieth century, Duke Kahanamoku, a Hawai`ian of royal descent, emerged as an Olympic gold medalist in swimming and a champion of surfing who pretty much single handedly popularized the sport worldwide.

Duke Kahanamoku’s draft card

National Archives Identifier: 641774

Kahanamoku won a gold medal in the 100-meter freestyle and a silver medal in the men’s four by 200-meter freestyle relay at the 1912 Summer Olympics in Stockholm, Sweden. At the 1920 Summer Olympics in Antwerp, he won gold medals in the 100-meter freestyle and in the relay, and he won a silver medal in the 100-meter freestyle at the 1924 Olympics in Paris. Between the Olympic games, he traveled the world giving swimming exhibitions, and he also showed off his surfing skills and wowed the world with his prowess. He is credited with turning the Australians onto the sport.

Statues of Kahanamoku have been built in many seaside cities around the world, but the most appropriate stands on Kuhio Beach in Waikiki in Honolulu. Posed before his surfboard with his arms outstretched, Duke welcomes everyone to the beach. Admirers regularly drape Kahanamoku’s arms with colorful leis.

In July 2021, American surfer Carissa Moore won the Olympic gold medal in surfing in the waters forty miles from Tokyo. It was the first time the sport was included in the summer games. When she returned to her home in Honolulu, one of her first stops was Kuhio Beach, where she offered leis to the statue of Duke Kahanamoku, who had inspired her to surf when she was a child.

Duke Kahanamoku at a Red Cross benefit in Brooklyn, NY Source: NARA’s Text Message blog |

Duke and surfboard Source: NARA’s Text Message blog |

Duke in Waikiki Source: NARA’s Text Message blog |

E Ai Kakou

Kaira Grace Pan’s

recipe for

Poke Me Ke Aloha

Source: Obama White House Archives

Between 2012 and 2016, First Lady Michelle Obama hosted five Kids’ State Dinners. Children from all fifty states submitted more than 6,000 Healthy Lunchtime Challenge recipes, and more than 270 young people and their families were welcomed to the White House.

Kaira Grace Pan was nine when she won the 2016 Healthy Lunchtime Challenge for the state of Hawai‘i. Her recipe for Poke Me Ke Aloha includes ulu, tofu, edamame, and quinoa. Her winning recipe includes Native Hawai`ian, Asian, and contemporary culinary elements, making it a fitting tribute to the multicultural heritage of her home state.