Archives Experience Newsletter - July 18, 2023

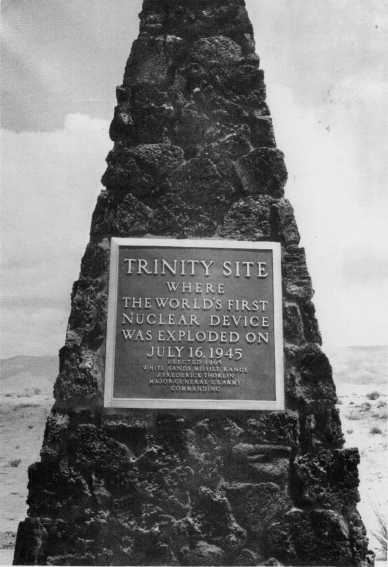

Trinity

You know the saying about two people being able to keep a secret, right? What about hundreds of people? Because that’s exactly what happened during World War II when the United States was in a race against the Axis Powers, particularly the Nazis, to develop an atomic weapon.

To pull off this feat, the U.S. government brought together some of the best minds in a generation: Albert Einstein, Enrico Fermi, and J. Robert Oppenheimer. Although the project employed hundreds of thousands of people, only a few dozen knew exactly what was going on when the first weapon was tested on July 16, 1945.

The best place to hide a secret is in plain sight…

In this issue

History Snack

Atomic Towns

The Manhattan Project is often thought of as a misnomer, but the project’s first office was actually at 270 Broadway in New York City. When the feasibility of an atomic weapon was proven, the project received an initial budget of $500 million directly from President Roosevelt, and aggressive recruitment of both scientists and construction workers began.

Now, the project had a problem. Hundreds of scientists were being recruited, but where would they all work to ensure, first, that their research and development would be a closely guarded secret; and second, that the site was remote enough to develop and test the deadliest weapon the world had yet seen? The answer was to hide the Manhattan Project in plain sight.

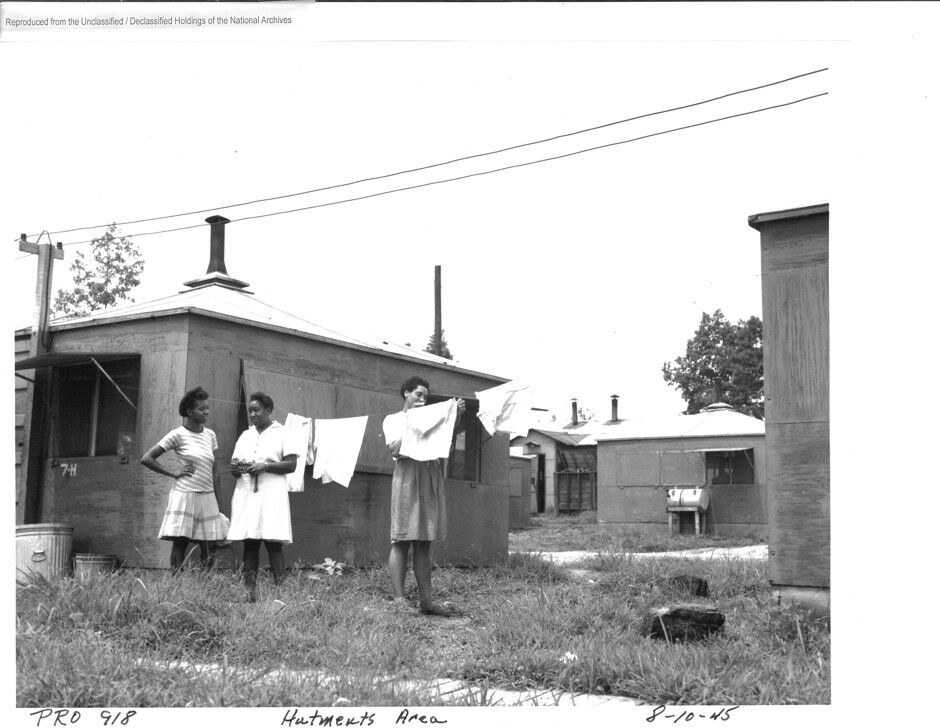

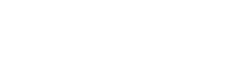

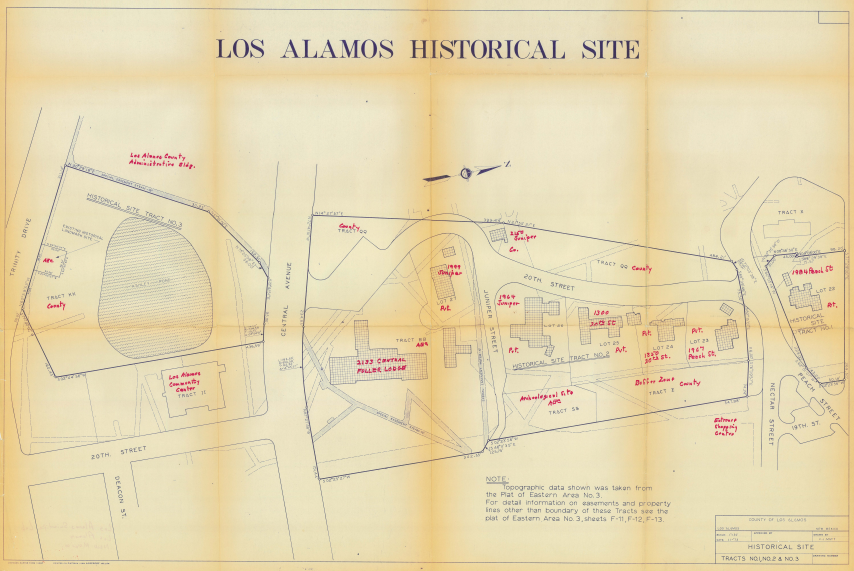

In 1942, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers began construction on what would be called “atomic towns.” The site selections were well-vetted. These towns, which popped up almost instantly, were located in remote areas that allowed maximum security and secrecy. The isolation also allowed for civilian safety; in the case of radiation leaks, accidents, or attacks by German bombers, damage would be contained to the laboratory and research sites only. These atomic towns did not appear on any maps, but we now know that they were located at Los Alamos, New Mexico (wartime population 6,000), Oak Ridge, Tennessee (wartime population 75,000) and Hanford, Washington (wartime population 50,000), to name a few.

Map of Los Alamos historic site

Construction worker camp at Hanford, Washington

On the surface, life in these towns seemed normal. People went to work, did their shopping, sent their children to school, and attended social events. Drop an unsuspecting visitor in one of these towns, and it wouldn’t have been immediately obvious to them that workers there were developing an atomic bomb.

Tulip town market, Oak Ridge, TN

National Archives Identifier: 1687939

But just because life looked normal didn’t mean it was. The security measures in these towns were heightened, and their true purpose was to control the lives of their leading scientists to ensure maximum secrecy. The sites were fully militarized. Armed guards and a barbed wire fence surrounding the entire community. On-site accommodations were provided for workers and their families, but the little leisure time allowed was strictly controlled. At Los Alamos in particular, no outside residents were permitted as employees, even in civilian roles, and the scientists could not have contact with anyone outside their worksite, not even relatives. Mail was censored, and scientists were not allowed to travel more than 100 miles from their towns. Encounters on the outside, however casual, had to be reported in detail to superiors immediately upon return.

Unsurprisingly, scientists were sworn to absolute secrecy. Most residents of these atomic towns, including the construction workers who built them, had no idea what was going on there. Residents lived in the dark, with a vague sense that something was happening. No one knew (yet) what nuclear weapons were, and the government’s policy was never to give an explanation.

“Site X”

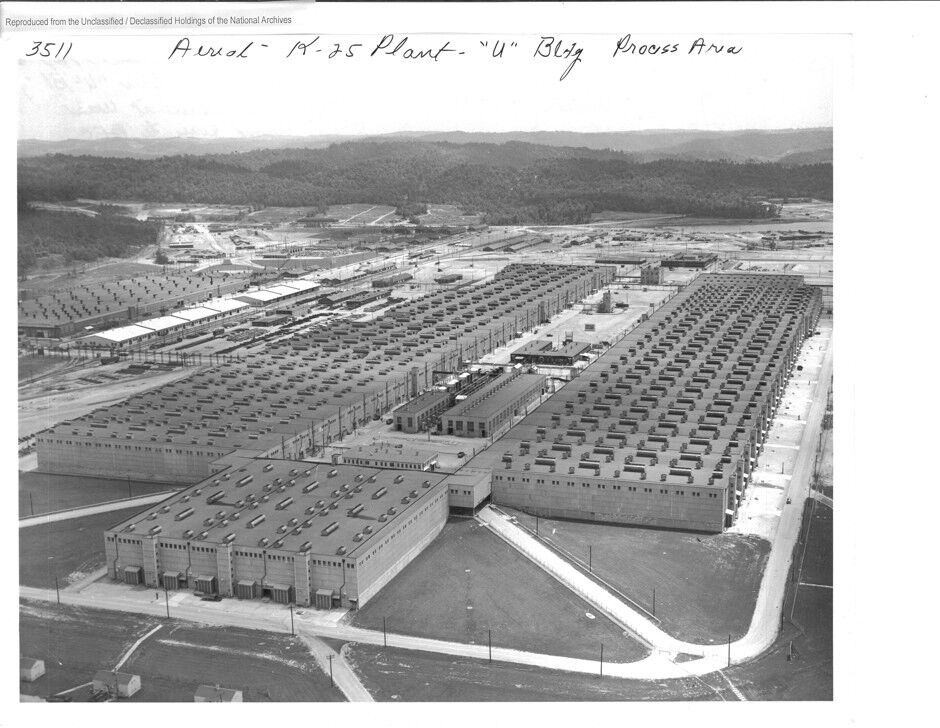

The town at Oak Ridge, Tennessee, was not given that name until after the war’s end. The area was known as “Site X” and was the home to uranium enrichment plants, liquid thermal diffusion plants, and a prototype of a plutonium production reactor.

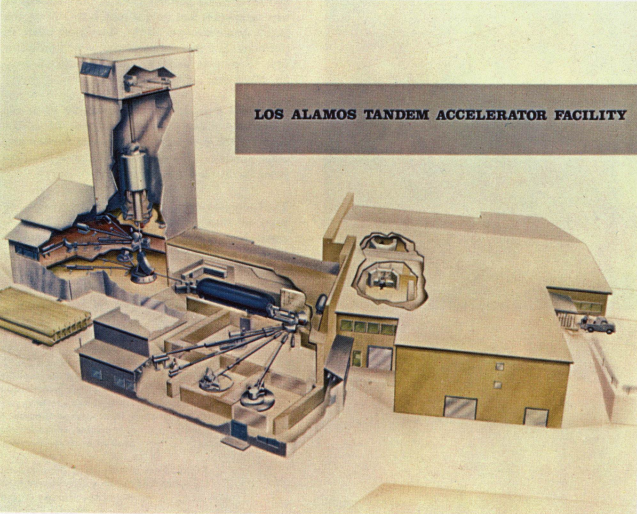

Site X was critical to the development of the bomb. The plants in Tennessee began working on purifying uranium, but they quickly came under pressure from Oppenheimer’s lab at Los Alamos when he called for three times the amount of uranium that had originally been anticipated. Another plant was set up for the diffusion process. It was built by 25,000 construction workers and was over 44 acres in size. At the time, it was the largest building under one roof in the world. The products from Site X would be sent to the Hanford, Washington site.

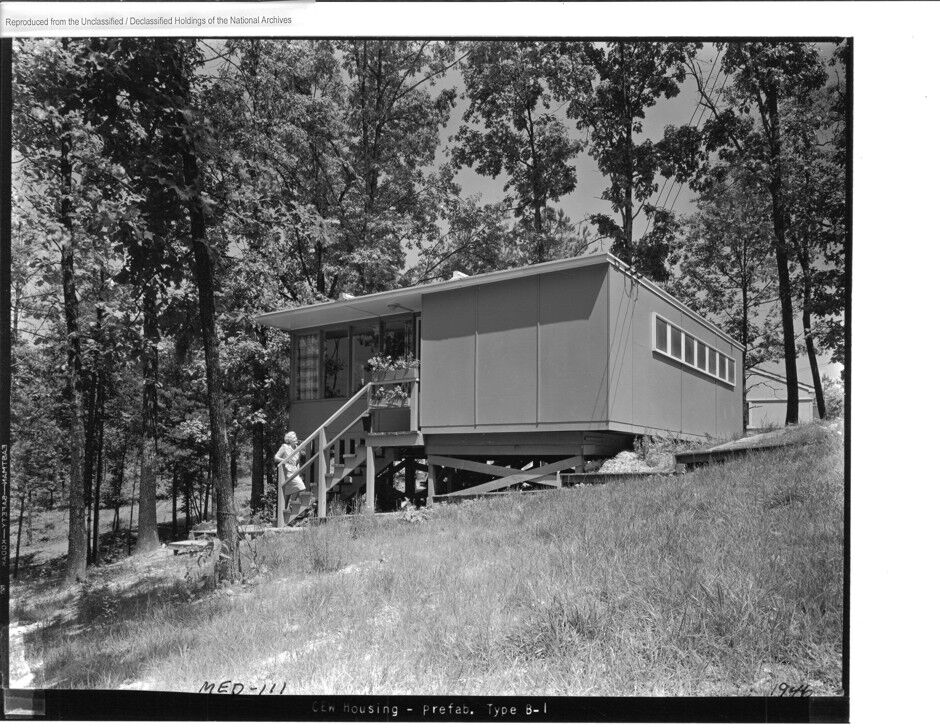

The government had planned Site X to be a town home to 13,000, but the population exploded to more than 75,000. One of the legacies of atomic towns is that they were one of the first to use prefabricated houses and architecture. The prefab houses of Site X, known as “Alphabet Houses,” were made off-site and had predetermined floorplans. A houses were two bedrooms, B houses had flat-top roofs, C houses had extra rooms, and D houses came with a dining room. At the height of construction, 30 to 40 families moved into new houses each day.

<

These prefab houses were also early indicators of a postwar architectural trend to come, a style now known as “midcentury.”

Gadget

At 5:29 a.m. on July 16, 1945, residents of Los Alamos, New Mexico, felt a shockwave from 100 miles away and saw a mushroom cloud rise seven miles into the air. They were told that a “high explosive” was accidentally detonated, and nothing else.

Eyewitness account of the Trinity explosion

National Archives Identifier: 594933

What they had really witnessed was the nuclear age beginning with Robert Oppenheimer’s “Trinity” test. “Gadget,” the world’s first nuclear bomb, was dropped at the Alamogordo Bombing and Gunnery Range, but Oppenheimer called the site “Trinity,” and the name not only stuck but became the site’s official code name. Gadget was extremely similar to the bomb eventually used on Nagasaki, Japan, and was a large, round, plutonium implosion device—more powerful than the uranium bomb used on Hiroshima.

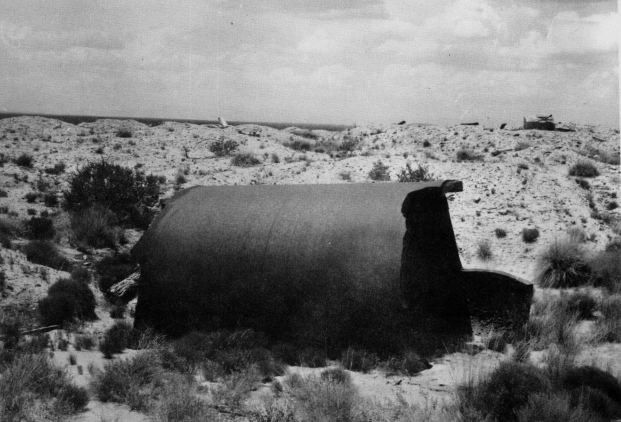

“Jumbo” atomic device being positioned for Trinity tests in NM

National Archives Identifier: 558570

Gadget was detonated from afar using explosives, but there was one particularly harrowing moment during testing. As Gadget was being raised to the top of its tower, it came partially unhinged. For a few terrifying seconds, the device swayed while onlookers contemplated the possibility that the bomb would fall from the tower and detonate. Luckily, Gadget was reattached and tested without further incident.

Remains of “Jumbo” container, which has since been vandalized

Radiation levels at Trinity are still 10 times higher than natural amounts. The blast caused untold and unknown damage to a “downwinder” community called Tularosa, which has never been officially studied. In subsequent nuclear tests throughout the 1950s, nuclear testing sites included “Doom Towns,” complete with houses and mannequins, to study the effects of the blasts and radiation on people.

Revelation

On August 6, 1945, the secret of the atomic towns was revealed to all when the U.S. dropped the first-ever nuclear bomb on the Japanese city of Hiroshima. Reactions of atomic town residents were mixed, alternating between pride that they had worked on the weapon that ended the war and horror at the damage the atomic bomb did. Another bomb was dropped on Nagasaki three days later on August 9.

Mary Lowe Michel, who was employed as a typist in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, said:

“The night that the news broke that the bombs had been dropped, there was [sic] joyous occasions in the streets, hugging and kissing and dancing and live music and singing that went on for hours and hours. But it bothered me to know that I, in my very small way, had participated in such a thing, and I sat in my dorm room and cried.”